It started with a simple frustration. I wanted to glance at my iPhone and instantly know when the next prayer was, without unlocking the phone or opening an app. The official MyMasjid app existed and it did the job, but its widgets felt like an afterthought. Black text on a white background. A basic table layout. No visual hierarchy, no personality, no consideration for the fact that this is something Muslims look at dozens of times every single day.

For something so central to daily life, especially during Ramadan when you are tracking Fajr at 4 AM and Maghrib for breaking fast, I wanted something that felt intentional. Something that matched the care Apple puts into their Weather or Fitness widgets. So I did what any curious developer would do: I opened Chrome DevTools, started tracing network requests, and began building my own.

The Problem with Existing Solutions

Before diving into the build, I spent time understanding why existing prayer time widgets felt inadequate. Most apps treat widgets as a checkbox feature. They expose the same data they show in the app, just smaller. But widgets are fundamentally different from apps. You cannot tap into them to explore. You cannot scroll. You get one glance, maybe two seconds of attention, and the information needs to be instantly digestible.

The official MyMasjid widget showed all five prayer times in a list. Technically accurate, but cognitively demanding. When I look at my home screen at 2 PM, I do not care about Fajr or Isha. I care about Asr, which is coming up next, and maybe Zuhr, which I should have already prayed. The widget should understand temporal context and surface what matters right now.

I also noticed that the existing widget made no distinction between Adhan time (when the prayer window opens) and Iqamah time (when the congregation starts at the mosque). For someone who actually goes to the masjid, this distinction is critical. You need to know both: when can I pray, and when should I arrive.

API Reconnaissance: Finding the Data

MyMasjid powers digital prayer time displays in mosques across Europe and beyond. Their platform includes a web dashboard at time.my-masjid.com where mosque administrators can update timings. I figured if there is a web interface, there is an API behind it.

I opened the Network tab in Chrome DevTools and started clicking around their dashboard. Within minutes, I had mapped out the core endpoints. The API was not documented publicly, but it was not protected either. No API keys, no authentication tokens for read operations. Just clean REST endpoints returning JSON.

struct MasjidConfiguration {

static let countryId = 2 // Denmark

static let cityId = 31 // Albertslund

static let masjidGuid = "e71c04a3-db20-4a9b-9cd2-c63c5970ffe7"

// API Endpoints

static let baseAPIURL = "https://time.my-masjid.com/api"

static let timingsEndpoint = "\(baseAPIURL)/TimingsInfoScreen/GetMasjidTimings"

static let countriesEndpoint = "\(baseAPIURL)/Country/GetAllCountries"

static let citiesEndpoint = "\(baseAPIURL)/City/GetCitiesByCountryId"

static let masjidsEndpoint = "\(baseAPIURL)/Masjid/SearchMasjidByLocation"

}The discovery process followed a logical hierarchy. First, I found /Country/GetAllCountries which returns a list of all supported countries with their IDs. Denmark was ID 2. Then /City/GetCitiesByCountryId gave me cities within Denmark. Albertslund, where my local mosque is located, was ID 31. Finally, /Masjid/SearchMasjidByLocation returned mosques in that city, each with a unique GUID identifier.

That GUID was the key to everything. Feeding it into /TimingsInfoScreen/GetMasjidTimings returned a goldmine: an entire month of prayer times, including both Adhan and Iqamah times for every prayer, plus metadata about the mosque itself like display preferences and Jummah timing.

Designing the Data Layer

With the API mapped, I needed to model the data in Swift. The response structure was nested but logical. At the top level, you get mosque details (name, address, coordinates), mosque settings (12 vs 24 hour time, DST handling, whether to show Hijri calendar), and an array of daily prayer timings.

struct MasjidData: Codable {

let model: Model

}

struct Model: Codable {

let masjidDetails: MasjidDetails

let masjidSettings: MasjidSettings

let salahTimings: [SalahTiming]

}

struct SalahTiming: Codable {

let fajr: String

let shouruq: String

let zuhr: String

let asr: String

let maghrib: String

let isha: String

let day: Int

let month: Int

let iqamah_Fajr: String

let iqamah_Zuhr: String

let iqamah_Asr: String

let iqamah_Maghrib: String

let iqamah_Isha: String

}Each day's entry contains the five prayer times plus Shouruq (sunrise), and critically, the Iqamah times which are set by the mosque administration. This is data you cannot get from astronomical calculation alone. It is human-curated, reflecting when that specific mosque actually starts congregation.

I built Codable models mirroring the JSON structure exactly. Swift's type system then guarantees that if the data decodes successfully, I have everything I need. No optional unwrapping scattered throughout the codebase, no defensive nil checks everywhere. The complexity is contained at the network boundary.

Understanding WidgetKit's Mental Model

iOS widgets do not work like regular apps. You cannot run code continuously or respond to events in real time. Instead, you provide iOS with a "timeline" of entries, each representing what the widget should display at a specific point in time. The system then renders these entries on your behalf, even when your app is not running.

This constraint actually led to better architecture. I could not be lazy and just fetch fresh data every time the widget appeared. I had to think carefully about when data actually changes and schedule refreshes accordingly.

struct Provider: TimelineProvider {

func getTimeline(in context: Context, completion: @escaping (Timeline<SimpleEntry>) -> Void) {

fetchAndBuildTimeline(guidId: MasjidConfiguration.masjidGuid, completion: completion)

}

private func buildEntry(from data: MasjidData) -> SimpleEntry {

let now = Date()

let calendar = Calendar.current

let components = calendar.dateComponents([.day, .month, .weekday], from: now)

guard let todayTiming = data.model.salahTimings.first(where: {

$0.day == components.day && $0.month == components.month

}) else {

return errorEntry()

}

let prayerTimes = [

"FAJR": todayTiming.fajr,

"ZUHR": todayTiming.zuhr,

"ASR": todayTiming.asr,

"MAGHRIB": todayTiming.maghrib,

"ISHA": todayTiming.isha

]

let (nextPrayerTime, nextPrayerName) = calculateNextPrayerTime(from: prayerTimes, date: now)

// ... build and return entry

}

}For prayer times, the answer is elegant: the widget only needs to update when a prayer time passes. If Asr is at 3:37 PM, the widget showing "Next: Asr" is valid until 3:37 PM. After that, it should show "Next: Maghrib". So instead of refreshing every 15 minutes like many widgets do, I tell iOS to refresh one minute after the next prayer time.

let refreshDate = entry.nextPrayerTime.addingTimeInterval(60)

let timeline = Timeline(entries: [entry], policy: .after(refreshDate))This approach is both more accurate and more battery efficient. The widget updates exactly when it needs to, not on some arbitrary schedule that might miss the actual transition or waste cycles refreshing when nothing has changed.

The Jummah Edge Case

Friday prayers presented an interesting challenge. In Islam, the Zuhr prayer on Friday is replaced by Jummah, a congregational prayer with a sermon. The timing is different (mosques often have Jummah earlier than regular Zuhr), and conceptually it is a distinct prayer with its own significance.

The API handles this by providing a separate jumahTime field in the mosque settings. My widget needed to detect Fridays and swap the display accordingly. This was not just a data substitution; the entire visual treatment changes. Jummah gets a green gradient with crescent moon imagery, distinct from the warm afternoon palette used for regular Zuhr.

private func getImageName(for prayerName: String, weekday: Int) -> String {

// weekday == 6 is Friday in Apple's Calendar

if prayerName == "ZUHR" && weekday == 6 {

return "Jummah"

}

return prayerName.capitalized

}

// In the view layer, swap the row display

if weekday == 6 {

prayerRow("Jummah", time: entry.jummahAzanTime, activePrayer: activePrayer)

} else {

prayerRow("Zuhr", time: entry.dhuhrStartTime, activePrayer: activePrayer)

}Apple's Calendar API uses a somewhat counterintuitive weekday numbering where Sunday is 1 and Saturday is 7, making Friday equal to 6. These details matter. Someone glancing at their widget on Friday afternoon should immediately feel that this is Jummah, not just another Zuhr. The visual language reinforces the spiritual significance.

Intelligent Caching

Widgets have strict power and network budgets. Apple actively penalizes widgets that make excessive network requests. Since the API returns an entire month of prayer times in a single call, I implemented aggressive caching with smart invalidation.

class CacheManager {

static let shared = CacheManager()

let defaults: UserDefaults

init() {

defaults = UserDefaults(suiteName: MasjidConfiguration.appGroupIdentifier) ?? .standard

}

func cacheData(_ data: Data, for key: String) {

defaults.set(data, forKey: key)

}

func getCachedData(for key: String) -> Data? {

return defaults.data(forKey: key)

}

}The caching logic considers the Islamic day boundary. In Islamic tradition, the new day begins at Maghrib (sunset), not midnight. This has practical implications: after Maghrib, when someone checks their widget, they are thinking about tomorrow's Fajr, not today's completed prayers. So my cache invalidation triggers at Maghrib, fetching fresh data to ensure tomorrow's times are ready.

if let maghribDate = createDateForPrayerTime(maghribTimeString, on: now, in: timezone) {

if now < maghribDate && isSameDay(cachedDate, now) {

// Cache is still valid, use it

buildTimeline(from: decodedData, completion: completion)

return

}

}

// Cache expired, fetch fresh data

fetchMasjidInfo(guidId: guidId) { result in ... }I used an App Group to share the cached data between the main app and the widget extension. UserDefaults with a suite name lets both targets read and write to the same storage. The widget checks the cache first, validates that it is from today and that Maghrib has not passed, and only hits the network if necessary.

In practice, this means the widget makes one API call per day, typically in the evening. The rest of the time, it operates entirely from cache. Battery impact is negligible.

Visual Design: Making Each Prayer Distinct

The most visible differentiator from the official widgets is the visual treatment. I created distinct gradient palettes for each prayer time, designed to feel contextually appropriate:

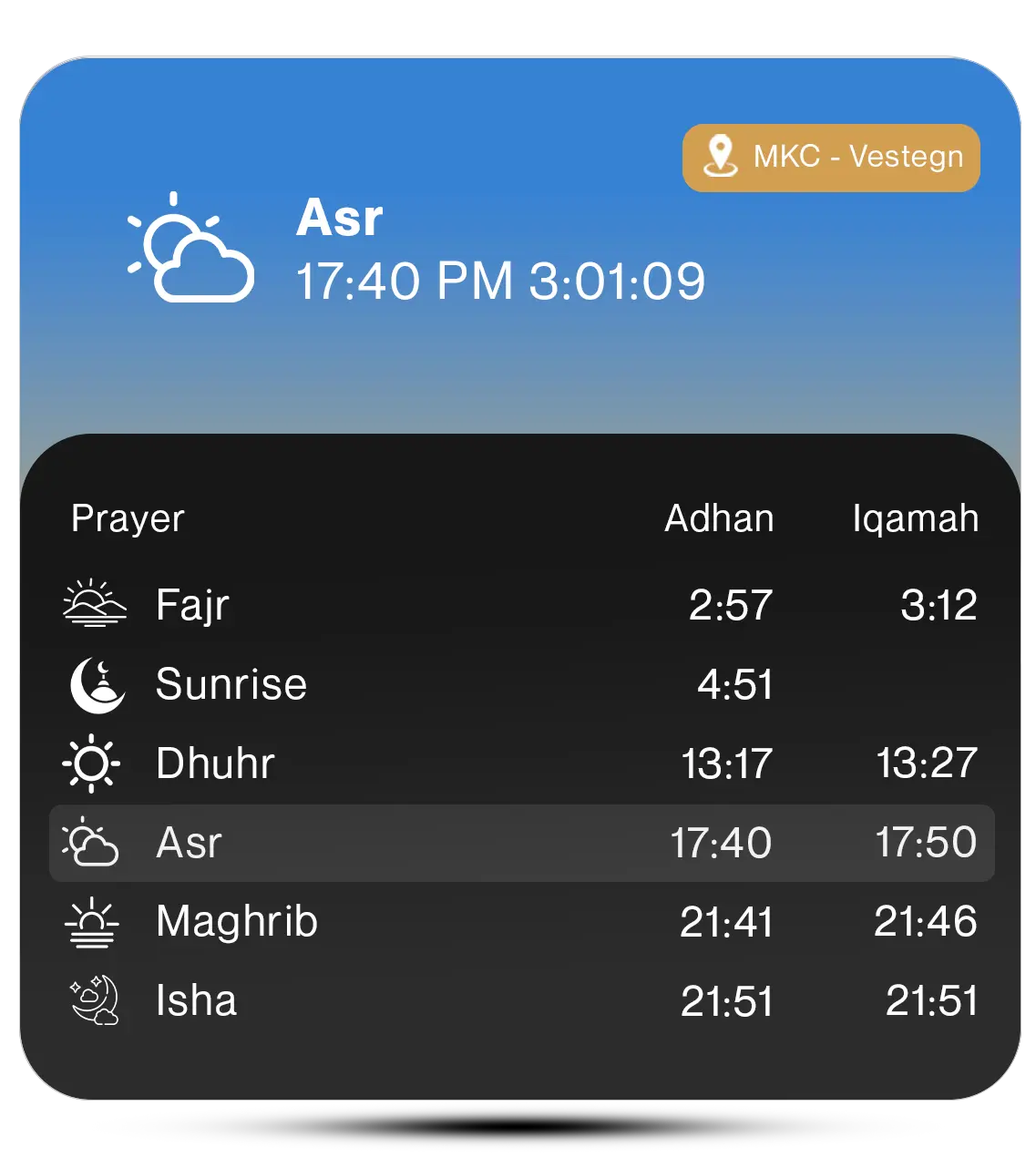

Fajr uses deep blues fading to lighter sky tones, evoking the pre-dawn darkness giving way to first light. Dhuhr gets warm yellows and soft whites, the bright midday sun. Asr transitions to warmer afternoon hues, golden hour approaching. Maghrib is the most dramatic, with purples, pinks, and oranges capturing the sunset. Isha returns to deep navy and dark blues, the night sky.

These are not arbitrary aesthetic choices. They create instant recognition. When you glance at your home screen and see that purple-pink gradient, you know it is Maghrib time without reading a single word. The color itself carries meaning.

I also created inverted variants for dark mode. Rather than letting iOS automatically invert colors (which often looks terrible), I manually designed dark mode versions of each asset. The naming convention is simple: Fajr becomes FajrInvert. The widget checks the system color scheme and loads the appropriate variant.

struct MediumWidgetView: View {

var entry: SimpleEntry

@Environment(\.colorScheme) var colorScheme

var displayedImageName: String {

colorScheme == .dark ? entry.imageName + "Invert" : entry.imageName

}

var body: some View {

HStack(alignment: .top) {

Image(displayedImageName)

.resizable()

.frame(width: 40, height: 40)

// ... rest of the layout

}

}

}Supporting Multiple Widget Sizes

WidgetKit supports several widget families: small, medium, large, and various lock screen accessories. Each size has different constraints and use cases, so I built five distinct layouts rather than trying to scale one design.

The small widget is ruthlessly focused. It shows only the next prayer name, the time, and a countdown. No clutter, no secondary information. You can read it in under a second.

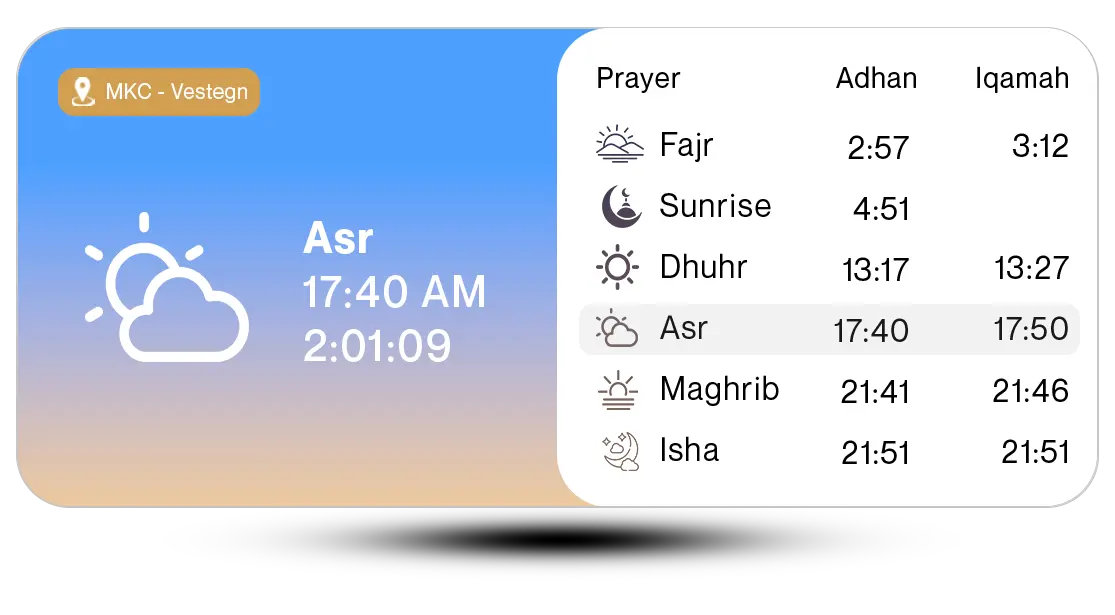

The medium widget adds context. The left side shows the next prayer with countdown, while the right side displays the full day's schedule. The currently active prayer (the one you should have prayed) gets a subtle highlight, providing gentle accountability.

The large widget goes comprehensive. It includes both Adhan and Iqamah columns, sunrise time, and the mosque name. This is for people who want the full picture without opening an app.

struct WidgetView: View {

var entry: SimpleEntry

@Environment(\.widgetFamily) var family

var body: some View {

switch family {

case .systemSmall:

SmallWidgetView(entry: entry)

case .systemMedium:

MediumWidgetView(entry: entry)

case .systemLarge, .systemExtraLarge:

LargeWidgetView(entry: entry)

case .accessoryRectangular:

AccessoryRectangularView(entry: entry)

case .accessoryCircular:

AccessoryCircularView(entry: entry)

case .accessoryInline:

AccessoryInlineView(entry: entry)

default:

SmallWidgetView(entry: entry)

}

}

}The lock screen widgets are minimal by necessity. The rectangular accessory shows next prayer and countdown. The circular accessory uses a gauge visualization. The inline accessory is text-only, appearing in the always-on display line.

Active Prayer Highlighting

A subtle UX detail that took some thought: highlighting the "active" prayer in the schedule view. The active prayer is not the next prayer, it is the current one. If Asr is coming up next, that means Zuhr is currently active (you should have prayed it already).

This requires reverse-calculation from the next prayer. I maintain an ordered list of prayers for regular days and a modified list for Fridays (swapping Zuhr for Jummah). Given the next prayer's position in this list, I step back one index to find the active prayer. There is wraparound logic for when the next prayer is Fajr, meaning Isha from the previous day is currently active.

func currentActivePrayer(nextPrayer: String, weekday: Int) -> String {

let order = (weekday == 6)

? ["Fajr", "Jummah", "Asr", "Maghrib", "Isha"]

: ["Fajr", "Zuhr", "Asr", "Maghrib", "Isha"]

guard let index = order.firstIndex(where: {

$0.caseInsensitiveCompare(nextPrayer) == .orderedSame

}) else {

return "Isha"

}

// Step back one index, with wraparound

let currentIndex = (index == 0) ? (order.count - 1) : (index - 1)

return order[currentIndex]

}The active prayer gets a subtle gray background highlight in the schedule table. It is not aggressive, but it creates visual hierarchy. Your eye naturally goes to the highlighted row first, then scans up or down for additional context.

Contacting the Official Team

After finishing the implementation, I put together a comparison document showing the existing widgets versus my redesign. The visual difference was stark. I sent an email to the MyMasjid team explaining what I had built, why I thought it improved the user experience, and offering to collaborate.

My pitch focused on the emotional dimension of prayer time widgets. This is not like checking the weather or your step count. For practicing Muslims, these five daily prayers structure the entire day. The widget is not just displaying data; it is serving as a gentle reminder of spiritual obligations. It deserves design attention proportional to its importance in users' lives.

I included screenshots of all widget sizes, both light and dark mode variants, and a brief technical overview of the architecture. I emphasized that the work was already done; they could integrate it without starting from scratch.

"The best interface is one that feels inevitable, like it could not have been designed any other way."

Lessons Learned

Building this project reinforced several principles that I keep coming back to in my work.

First, constraints breed creativity. WidgetKit's limitations (no continuous execution, no real-time updates, strict power budgets) forced me to think harder about when data actually changes and how to communicate information efficiently. The result is better than what I would have built without those constraints.

Second, domain knowledge matters. Understanding the Islamic day boundary, the significance of Jummah, the difference between Adhan and Iqamah: these are not technical requirements you find in a spec document. They come from being a user yourself, from caring about the problem space beyond just "display some times on screen."

Third, visual design is not decoration. The gradient palettes, the prayer icons, the dark mode variants: these are not polish added at the end. They are core to how the widget communicates. Color carries meaning. Hierarchy guides attention. Every visual choice either helps or hinders comprehension.

Finally, building in public creates opportunities. By documenting this work and reaching out to the official team, a personal side project became a potential contribution to a product used by mosques across Europe. The worst that could happen is they say no. The best case is collaboration on something meaningful.

Technical Summary

This project involved reverse-engineering an undocumented REST API using browser developer tools, implementing a WidgetKit timeline provider with prayer-time-aware refresh scheduling, building adaptive layouts across six widget families, handling Islamic calendar edge cases including Jummah and the Maghrib day boundary, creating a complete dark mode asset pipeline, and implementing intelligent caching with UserDefaults shared via App Groups. The result is a widget system that feels native to iOS while serving a deeply personal use case.